How does it work

en

English

English

Deutsch

Deutsch

Italiano

Italiano

19 December

This year marks ten years of the Microsoft Surface family of tablets, laptops, and hybrid computing devices. We caught up with Microsoft’s Ralf Groene, corporate vice president of Design, Windows and Devices, and Pete Kyriacou, corporate vice president of Devices, to talk about the milestone and what hardware means to a company that was born out of software.

‘I started at Microsoft in 2006,’ says Groene, ‘so obviously I didn't start in the Surface team. I remember a colleague showed us a graph that illustrated how in a couple of years, laptops would overtake desktops. The world was going mobile.’ To take advantage of this more touch-centred new world, the original Surface was developed hand in hand with Windows 8, launched in 2012 with a controversial ‘live tile’ arrangement of apps and icons that was designed explicitly for use with touch screens.

That first device was a tablet, announced in June 2012 as the first PC ever to be designed and distributed by the Seattle-based monolith. It was soon joined by the Surface Pro. Both were hybrid devices, with detachable keyboard/screen covers that turned the tablet into a slender laptop. The key competitor was, of course, the iPad, which had already been on the market for a couple of years.

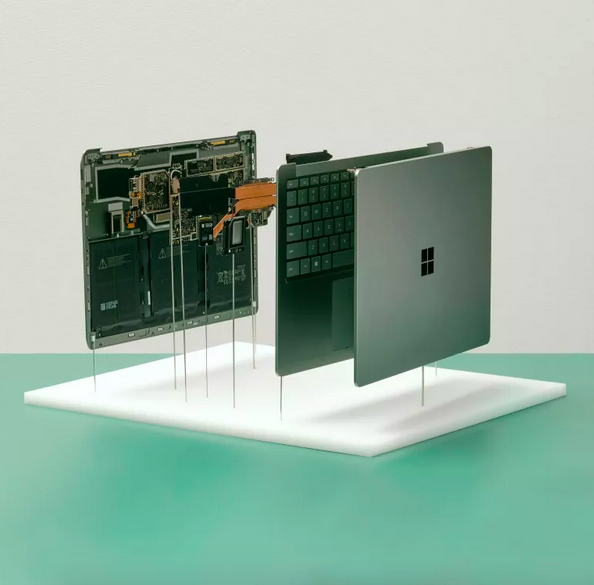

Groene points out that these devices were born in the early days of large-scale capacitive screens. ‘We wondered how much you needed the mouse and the keyboard,’ he says, ‘although of course a conventional laptop came later.’ As for form factor, although Surface has always used premium materials, it hasn’t strayed terribly far from the Platonic ideal of a laptop form.

‘It’s like when famous architects design a chair,’ Groene notes. ‘Do they do something whimsical? Do they do something fancy? We had to think how our values would be represented by a laptop.’ Microsoft’s software background drove the innovation, although Groene says the Surface Pen was essentially developed at a time when no software really made great use of it. Nor did divisions like Microsoft Office really embrace the potential for the touch screen.

‘The ability to fail fast is one of our attributes,’ notes Kyriacou dryly, not mentioning that for the first couple of years, the Surface division fell way short of its economic targets. The company persisted, nevertheless. ‘Its primary role is to lift the Windows eco-system up,’ says Kyriacou. In order to do this, the hardware team works hand in hand with chipmakers and other component suppliers to get bespoke silicon into the Surface line, all the better to accelerate elements like facial recognition.

The range expanded to incorporate the Surface Laptop, Studio, Hub, Book and Duo (the latter a folding phone that continues to improve). Groene cites the Surface Studio as an example of what he describes as a particular ‘moment of weightlessness’. The flagship desktop device fulfilled the design team’s vision for a ‘floating sheet of pixels’ in front of the user.

For Kyriacou, it was the Surface Pro 3 that marked the point the platform had really matured. ‘It was a full laptop, but also a pen tablet,’ he says, pointing out how long it took to refine the physical thinness of the devices. Neither designer can be drawn on what might come next. ‘A chair is designed through the behaviour of sitting, and a laptop through the behaviour of typing,’ Groene says. ‘It’s not the greatest experience for using a pointer, sketching or even note-taking.’

As a result, Microsoft seems happy to let different form factors exist as hubs for different activities. The suggestion that tablets would swiftly kill off laptops has proved wide of the mark. While innovations like the well-received Windows 11 gave computing a boost, so did more unpredictable events like the pandemic.

Groene admits to having a ‘closet full’ of new ideas. ‘The best technological objects become an extension of us,’ he says. ‘In the next five years, I’d predict that things will change so much more than in the last five years. Think of how money has evolved from being a tangible object into a virtual one. Data is not the same thing, of course, but it follows the same path.’

‘We’re well placed to blur the lines of technology so that people don’t notice them,’ Kyriacou adds, explaining that AI will be making big leaps in how sound and images are presented on things like video calls. On top of this, there’s a hint that we’ll be moving from a two-dimensional data environment into a three dimensional one.

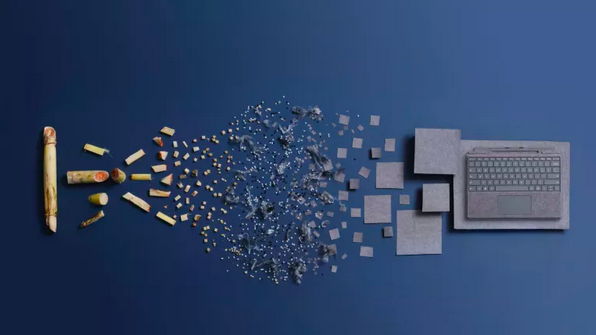

Finally, there’s the age-old issue of sustainability. ‘We’re committed to carbon reduction, but that’s very hard to achieve if you create hardware,’ Kyriacou says, pointing to an increase in bio-based materials in the current Surface line. ‘As a designer, I always enjoy making products with great quality materials,’ says Groene. ‘Things like leather and wood break in rather than wear out.’ Perhaps one day we’ll reach a point where hardware is mature enough to run practically anything, and the constant cycle of upgrades is a thing of the past. All our design embodies our business pillars – sustainability, accessibility, and security and privacy,’ he concludes. ‘These will be represented in the products we make.’